Today marks the centenary of the Senghennydd mining disaster, the worst ever in the UK, that claimed the lives of 440 men and boys. It was commemorated with various events in Senghennydd including the unveiling of a statue remembering all who died in Welsh mining accidents.

Many who died at Senghennydd in 1913 had travelled there from other parts of Wales, but you wouldn’t have known that from reading this morning’s Wasting Mule, which did a panel piece on someone who’d moved from West Sussex! Doesn’t the Mule realise that the whole point of a Welsh newspaper is to cover Welsh news, and other news from a Welsh angle? Senghennydd provided an opportunity for the Mule to live up to its claim to be the ‘National Newspaper of Wales’ by bringing together the various parts of the country; but no, the Mule, as ever, had to look at Wales from an English perspective.

I mention this because I was fortunate enough to take part in a little ceremony of remembrance myself on Saturday. Due to my wife and her sister being collateral descendants of Edward Jones Humphreys of Abergynolwyn who, by the time he died at Senghennydd – and by a route the ladies have yet to establish – was universally known as ‘Idrisyn’. When the local quarry closed he made his way south with his brother (wife’s taid), and their sister, who was there with her husband. (Click to enlarge image.)

The fact is that W ales in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries experienced considerable internal migration which, for whatever reason, is often neglected. Too many prefer to concentrate – a la Mule – on migration into or out of Wales. Of my eight great-grandparents four came up to Swansea from the west, Carmarthenshire and Cardiganshire, places like Meidrim and New Quay. Most of those who came to work in the local Bryneglwys quarry here in south Meirionnydd came from Montgomeryshire, Caernarfonshire or further afield.

ales in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries experienced considerable internal migration which, for whatever reason, is often neglected. Too many prefer to concentrate – a la Mule – on migration into or out of Wales. Of my eight great-grandparents four came up to Swansea from the west, Carmarthenshire and Cardiganshire, places like Meidrim and New Quay. Most of those who came to work in the local Bryneglwys quarry here in south Meirionnydd came from Montgomeryshire, Caernarfonshire or further afield.

Returning to Senghennydd, I cannot avoid saying that I am disappointed with the statue. (Click to enlarge.) Isn’t it a bit, well, unimaginative? Crass, even? And another thing, the two portrayed are obviously survivors of some tragedy or other, so how do they commemorate the dead? Don’t get me wrong, I’m not saying that a statue commemorating the dead has to be composed of corpses, but this statue looks like the kind of ‘heroic’ and inspiring public art that could be found in every shit-hole town in the Urals circa 1965. It’s almost a caricature of communist propaganda statuary. In profile, the miner holding the lamp even has a passing resemblance to Lenin!

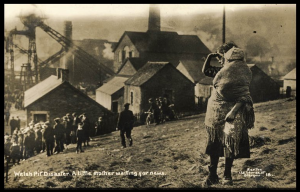

Surely the obvious inspiration for any statue commemorating the dead of Welsh mining disasters is that iconic image of the young girl, with the baby wrapped in a traditional shawl, shielding her eyes and looking into the distance. (Click to enlarge.) For these countless disasters may have taken the lives of thousands of  men and boys, but once dead they were – as my mamgu would say – ‘out of it’. The real suffering then was that of those who remained, the widows and orphans, so perfectly characterised by that sublime image. And, yes, it is also a memorial to the dead, for doesn’t she represent countless thousands of women and girls looking, waiting, for husbands, fathers, brothers who are never going to return?

men and boys, but once dead they were – as my mamgu would say – ‘out of it’. The real suffering then was that of those who remained, the widows and orphans, so perfectly characterised by that sublime image. And, yes, it is also a memorial to the dead, for doesn’t she represent countless thousands of women and girls looking, waiting, for husbands, fathers, brothers who are never going to return?

So why did the chosen statue have to be so in-yer-face? Did those who made the decision fear that visitors would be bewildered if confronted by anything needing a little thought and reflection? Isn’t that the whole point of art? Even public art?

A lot of sincere people in Senghennydd and the surrounding area have done a wonderful job of giving us another genuinely national institution. Making us all remember an important date in Welsh history, from a time and place that now seem so distant. They should all be proud of what they’ve done. Unfortunately . . . the centre-piece, the statue-memorial, was not an inspired choice. I’m sorry, folks, it was the wrong choice.