A Guest Post by ‘Blodyn Tatws’

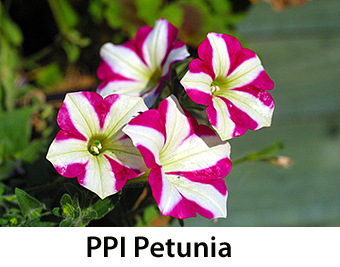

(Illustrations supplied by ‘Green Fingers’ Jac showing some of the gems you might encounter at the Garden)

The National Botanic Garden of Wales germinated as an idea in the 1990s and opened its gates to the public in May 2000. In common with so many of the other projects which saw the light of day under Tony “Things can only get better” Blair, it was sold to the public on an entirely unrealistic prospectus that it would become financially self-sustaining and shower economic benefits on Wales. It has never come close to achieving either of those objectives, and it never will.

To what extent the Garden can claim to be a national garden for Wales is also debatable, and it bears all the hallmarks of those countless third sector charities and trusts whose primary purpose seems to be to find something to do for members of the British establishment now that the market for sahibs and memsahibs has dried up.

Faced with low visitor numbers and dependent on annual subsidies from the Welsh Government and Carmarthenshire County Council, the Garden is now attempting a new throw of the dice to reverse its fortunes with a £6.7 million scheme based on a truly weird reading of Welsh history, which on closer inspection seems to have rather more to do with celebrating the history of merchant banking and the arcane world of the City of London.

UP THE GARDEN PATH

In June of this year, Carmarthenshire’s county councillors were treated to a 30 minute Powerpoint presentation by Dr Rosie Plummer, Director of the National Botanic Garden of Wales, as she took them on a whistle stop tour of claims, few of which were backed up by evidence and some of which simply don’t stand up to scrutiny.

Dr Plummer is nothing if not enthusiastic, and after a few words in Welsh (Rosie is proud of the O Level she took when she moved here), the rest of the spiel sounded like a games mistress addressing the Roedean junior lacrosse team with a sideline in corporate bullshit-bingo doublespeak. Our Rosie is very fond of words such as terrific, fantastic, cutting-edge, collaborative, strategic, tremendous and massive. “We are strategic!” she exclaimed at one point in what she obviously considered to be a slam-dunk argument, and the councillors duly gave her warm applause.

In an oblique reference to an earlier row about the Garden’s attitude towards the Welsh language, Dr Plummer declared that the Garden was massively respectful of the Welsh language, but failed to explain why her marketing manager had effectively told a well-known local broadcaster to bugger off when she asked politely for a bilingual version of a newsletter, or why the Garden had taken to putting up English-only signs to advertise various events.

MORE DOSH, PLEASE

Rosie was clearly much too well brought up to mention to rank-and-file councillors that she would be heading back to County Hall shortly to ask the council’s top brass for some of the cash for the £6.7 million scheme, an extension of the garden’s £1.3 million interest-free loan and a commitment to renewing the council’s annual subsidy.

By the by, there is also an interesting arrangement with the council whereby if the local authority ever sells three farmhouses currently occupied for free by the Garden, the capital rec eipts will go to the Garden, rather than the council.

eipts will go to the Garden, rather than the council.

And so, a couple of weeks later the Executive Board of Carmarthenshire County Council sat down to consider Rosie’s request. To its credit, and for the first time in recorded history, the word “consider” did not mean “rubber-stamp”. The council decided that future funding of the Garden should be dependent on a less cavalier attitude to the Welsh language, and that Dr Plummer should consider offering all-year discounted entry tickets to the local peasantry rather than allowing them in once a year for free in January when there is nothing to see.

If that was not embarrassing enough, the council also opined that the Garden needed to become more financially self-sustaining by attracting families and improving its marketing.

WELSH NOT

For several weeks all went quiet, but the leopard was not about to change its spots, and at the end of July it emerged that Dr Plummer had refused to meet representatives of Cymdeithas yr Iaith unless they provided their own interpreter at their own cost, adding that she would be willing to participate in such a meeting only as long as this process did not restrict the free exchange of ideas.

Separately, Dr Plummer told Cymdeithas that they should stop sending her e-mails in Welsh as English was her preferred language. When it was pointed out to her that the garden was committed to providing a service in Welsh under its language policy, Dr Plummer replied that the policy had been entered into voluntarily.

When the BBC tried to interview her about this, they were told that Dr Plummer’s busy schedule meant she had no time.

Cymdeithas has now written to Carwyn Jones to remind him that his government’s agreement on continued funding of the Garden contains conditions about the use of the language, and asking him to take steps to make the Garden meet its commitments.

Being the National Botanic Garden of Wales does not extend to paying anything more than lip service to the Welsh language or culture, and in reality it is much more interested in marketing itself to visitors from England.

Visitor numbers have been on the slide since Dr Plummer took over the running of the Gardens. The Garden is understandably reluctant to publish details, but according to a council report there were just 147,000 in the year to March 2015, despite 2014 being an unusually warm summer. That works out at about 400 per day. Back in 2009-10 income from admission fees was £445,000. In 2013-14, the most recent year for which published accounts are available, it was down to just £368,000. In 2013-14 the Garden received subsidies and grants from national and local government to the tune of £1,335,000, and without that and dipping into its reserves, the Garden would have to close its gates for good.

The closest Dr Plummer got to talking about visitor numbers in her pep talk to councillors was a picture of a little girl skipping for joy, but she was in no doubt that the Garden was vital to the local economy.

A more realistic picture of what visitors think of the Garden can be gained from Tripadvisor. Some enjoy their days out, and some are positively ecstatic, but then they would probably have given rave reviews to Basil and Sybil after a weekend at Fawlty Towers.

More worrying for the Botanic Garden is a thread which runs through most of the less positive reviews: this is a Garden which suffers from a distinct shortage of plants, with vast areas given over to grass, and a surprisingly shabby entrance area.

“It was all rather drab, and that was on a bright day,” said one visitor, while a couple of others noted their disappointment after a trip in March to see what the Garden’s promotional literature said would be 50 kinds of daffodil. Others complained of stale bara brith and weeds in the vegetable garden.

As amateur gardeners in Carmarthenshire know, unless you have a very favoured spot, most of us won’t see daffs in our gardens much before the end of March.

Mawrth a ladd, Ebrill a fling (March kills and April flays), says the old Welsh proverb. And they knew what they were talking about.

But Dr Plummer and her board have a big idea to transform the Garden’s fortunes.

A VISION

Dr Plummer’s presentation did include a reference to a £6.75 million project called “Middleton: Paradise Regained” (geddit, all you readers with English A Levels?) which has won initial funding from the National Lottery and a pledge of around £1.4 million from a businessman called Richard Broyd, the Mercers’ Company in the City of London and a couple of other charities.

The lottery grant was awarded in 2014, but the Garden is still about £5 million short of its target, and Dr Plummer warned that if the additional funds could not be found, there was a risk that the dosh could go to Kent.

If the project does get the go-ahead, it will join the once state-of-the-art bio sciences centre a t the site in Llanarthne, now unoccupied and looking for new tenants. It was built under the Welsh Government’s disastrous Technium scheme which was enthusiastically overseen by Cllr Meryl Gravell, the veteran former leader of the county council. Technium may have gone the way of Nineveh and Tyre in an orgy of what in some cases amounted to large scale fraud, but Meryl is still with us and is enthusiastically backing her new friend Rosie.

t the site in Llanarthne, now unoccupied and looking for new tenants. It was built under the Welsh Government’s disastrous Technium scheme which was enthusiastically overseen by Cllr Meryl Gravell, the veteran former leader of the county council. Technium may have gone the way of Nineveh and Tyre in an orgy of what in some cases amounted to large scale fraud, but Meryl is still with us and is enthusiastically backing her new friend Rosie.

Dr Plummer was pretty miffed about the first round of criticism of the Garden’s attitude towards the Welsh language in April, and issued a regal statement at the time to tick off the ungrateful locals:

“It is therefore enormously disappointing to be subject to such vigorous approaches that largely seem to overlook the very wide range of ways in which the garden actively contributes to bringing the unique importance of Wales to everyone who visits”, she declared.

So how Welsh is the garden and its vision for the 21st century?

CARMARTHENSHIRE OLD SPICE

Rather than spending a bit of time and money on those planty things and weeding, the great and good who run the place have hit on the idea of putting a lot of the site under water and doing a bit of archaeology to recreate a vision of Regency England Wales which will somehow incorporate the massive glass and steel dome designed by Norman Foster when he was in his glass and steel dome phase (see the Berlin Reichstag).

This historical justification for this is set out in a gushing press release to celebrate the backing of the Heritage Lottery Fund. The project aims “to tell the story of more than 250 years of East India Company influence that shaped the landscape of this part of Wales”, it purrs.

According to Rob Thomas, the Garden’s Head of Development, this is an “incredible story of pirates, plague and plants for health”, set at a time “when nutmeg and mace were worth more than their weight in gold”.

As we shall see, this is indeed a truly incredible yarn.

The chair of the HLF’s Welsh committee added that the project would help people learn about the history of the site and “the little known links the East India Company had to the area”.

So little known that they had escaped the attention of everybody else, including the late Dr John Davies, whose magisterial History of Wales does not contain a single reference to the Company or its influence on Wales.

A HISTORY LESSON

As far as the Garden is concerned, the history of the site began in the first half of the 17th century when the estate was bought by a Mr Henry Middleton.

The Middletons, or Myddletons, were municipal bigwigs in Chester under the Tudors, possibly originally from Oswestry, and a couple of them spotted an opportunity to cash in on the burgeoning spice trade under Elizabeth I. The most famous of these was Sir Henry Middleton who led a series of very lucrative and often violent expeditions to Asia. Sir Henry died childless after his final adventure, and his money was distributed among the large Middleton brood.

led a series of very lucrative and often violent expeditions to Asia. Sir Henry died childless after his final adventure, and his money was distributed among the large Middleton brood.

The Middletons’ association with the East India Company appears to have stopped at the death of Sir Henry, who as far as we know never went anywhere near Llanarthne. The Henry who bought the estate was probably a nephew.

The extent of the estate’s links with the East India Company up to the end of the 18th century was therefore that it was once owned by someone whose uncle made a lot of money out east.

Henry built a house on the site, and eventually the Middletons fizzled out. The Gwyns of Gwympa succeeded, but they lived beyond their means and the estate came up for sale in 1789 when it was acquired by William Paxton.

MONEY BAGS

Paxton was a Scot who rose up through the ranks of the East India Company to become Master of the Bengal Mint. In common with other Brit officers of the company, he amassed a huge fortune while running bits of India, and he ran a very lucrative sideline in helping other ex-pat plunderers to transfer their money back to Blighty.

Thus, it is claimed, Paxton laid the foundations of what was to become merchant banking, a branch of the banking industry which eventually morphed into investment banking, or as it is sometimes popularly known, casino banking.

Paxton’s main hobby was money, and there is nothing whatsoever to back up the Garden’s claim that the story of the estate is a tale intertwined with nutmegs, cloves and cinnamon.

East India Company men who made lots of money were known as ‘nabobs’ back home, and were about as popular with people at the time as investment bankers are today, although unlike their modern counterparts, they tended to wreck only the economies of other countries.

Nabobs generally liked to spend a few years out in India accumulating as much cash as they could before heading for home, where they would build mansions and buy their way into politics. Just like many modern Conservative Party donors, in fact.

This is exactly what Paxton did. Although he had never set foot in Wales before, he ended up buying the estate at Llanarthne in 1789, and shortly afterwards work began on a new neo-classical mansion.

The old Middleton Hall was turned into a farmhouse and then demolished, with much of the fabric being recycled for use in Paxton’s building projects. A study a few years back by the National Botanic Garden concluded that very little of the old house  remained to be uncovered apart from some foundations and bits of rubble, and yet uncovering what is left is one of the ideas behind the £6.7 million project.

remained to be uncovered apart from some foundations and bits of rubble, and yet uncovering what is left is one of the ideas behind the £6.7 million project.

Having built himself a house, Paxton turned his attention to the grounds, which he improved with a series of lakes and waterfalls.

His attempts to break into politics were less than successful, and he notoriously spent £15,000 (almost £500,000 in current values) on food and drink in the 1802 election trying, unsuccessfully, to become MP for Carmarthen. His investment paid off the following year, however, and he held the seat briefly until 1806.

To the horror of the National Dictionary of Biography, Paxton was the subject of scurrilous leaflets written by one of Jac o’ the North’s spiritual forbears in the 1807 election. There he was described as “an upstart nabob heedless of the interests of our native land”, a description which could be applied to a good many modern Tory and Labour MPs.

Paxton died in 1824, and the estate was sold on to a family which had made its fortune in the slave plantations of the West Indies, although that’s a bit of the garden’s history we are unlikely to be told about.

Architecture is a matter of taste, and Paxton’s house was relatively modest by the standards of the day. It was joined in the 19th century by a large number of other mansions of varying degrees of architectural merit dotted around Carmarthenshire, most of which are now long gone, ruined or in the advanced stages of decay.

Carmarthenshire proved to be not very fertile soil for the imported landed gentry, and Llanarthne was no exception.

Paxton’s house changed hands a couple of times before it was destroyed by fire in 1930. Only the servants’ wing survived, with the shell of the main house being bulldozed in the 1950s. The carefully restored servants’ quarters are, of course, out of bounds to the visiting public and now the domain of Dr Plummer.

The lakes were filled in just over a century after they were dug, and the county council became the new owner. There were no Meryl Gravells or Mark James’s around at the time, and so the estate was parcelled up into seven small farms which were then leased to families who wanted to get a foothold on the farming ladder.

PARADISE LOST AND REGAINED?

For just over sixty years, the Middleton estate reverted to being just a piece of rural Carmarthenshire, home to Welsh-speaking families who no doubt all had their own veg plots and modest gardens, only for the lot to be swept away in the New Labour era.

The life and work of the Welsh families who farmed on the site of the Garden will not feat ure in the “Paradise Regained” project which will instead celebrate colonial exploitation and the debt the world owes to merchant bankers.

ure in the “Paradise Regained” project which will instead celebrate colonial exploitation and the debt the world owes to merchant bankers.

Or as the Garden’s Head of Development, Rob Thomas, so eloquently put it, this “incredible” story spans “a period of 250 years of international trade from the times of barter and exchange to the establishment of international lines of credit and investment banking; the forging of the blueprint for our current capitalist system; and, in the hands of Sir William Paxton, the formation of modern investment banking.”

For any visitors wondering why the garden does not invest more in plants, the answer would seem to be that there is not enough money left after paying the salaries of all those spin doctors and heads of development.

It is no doubt purely a coincidence that the Garden’s trustees are headed up by an investment banker, Mr Rob Joliffe, who is currently Head of Emerging Markets for UBS, the Swiss banking giant, or that the funders include the Mercers’ Company, one of those arcane City of London old boys’ institutions.

Quite how any of this bears out Dr Plummer’s claim that the objective of the garden is to bring “the unique importance of Wales to everyone who visits” is anyone’s guess.