![]() This piece was unplanned until, on Tuesday morning, I woke, bleary-eyed, to find a DM waiting from a regular source alerting me to a piece in the Spectator (PDF version) connecting our village with slavery! This followed an earlier piece in the Telegraph (PDF version).

This piece was unplanned until, on Tuesday morning, I woke, bleary-eyed, to find a DM waiting from a regular source alerting me to a piece in the Spectator (PDF version) connecting our village with slavery! This followed an earlier piece in the Telegraph (PDF version).

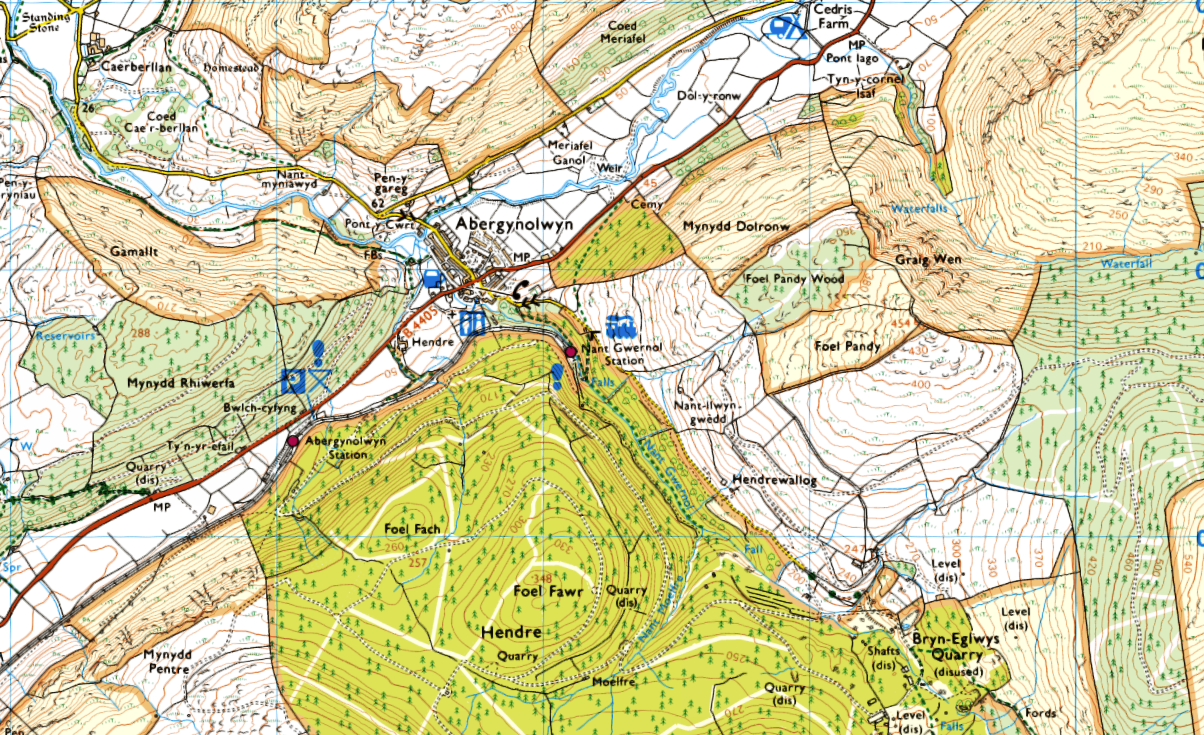

It all links with the UNESCO Slate Landscape of Northwest Wales project. I was involved locally in that project, and following the recent unwanted publicity I feel it’s time to give an alternative view.

And this is my own, and very personal, view.

◊

A BIT OF HISTORY

The first exploitation of the slate reserves at Bryneglwys was undertaken by John Pughe, when he took out a lease with local landowner Lewis Morris. Pughe, from Aberdyfi, already worked a few mines in the area.

Among these enterprises was the famous Dylife lead mine, in the high, empty country between Machynlleth and Llanidloes. Dylife attracted a number of workers from the Cardiganshire mines.

There’s little left in Dylife today, just scars of its industrial hey-day, plus a few houses and the Star Inn. But at its height, almost 200 years ago, it was a community of some 1200 people.

My wife tells me she recalls reading that Pughe died relatively young and his widow then sold the business. It passed through a few hands before being bought by the McConnel family of Manchester in 1863. I shall return to this period of the Bryneglwys quarry later.

The third chapter belongs to Henry Haydn Jones, who was born in Rhuthun, in the same year the McConnels bought Bryneglwys quarry. His father died when he was 10, which led to his mother returning to Tywyn.

Young Henry worked for his uncles J and D Daniel in their ironmongery business on Tywyn High Street. He obviously prospered, because in 1911 he bought the quarry and much of the village.

The year before, 1910, he had been elected Liberal Member of Parliament for Merioneth. And was to remain the local MP until 1945, when he stepped down as Sir Henry Haydn Jones.

Sir Henry kept the quarry open long after it was economically viable. Perhaps because he had a greater affinity with the community than the previous owners.

◊

THE MCCONNELS

The previous owners were of course the McConnel family, three of the sons of James McConnel, cotton mill owner of Ancoats, Manchester.

The reason the McConnels bought Bryneglwys quarry in 1863 was because the Union blockade of Confederate ports meant that little or no cotton was reaching Manchester.

So let’s state this clearly. The American Civil War meant that the McConnels had to find other ways to make money. They did not come to Wales as philanthropists.

They came to an area they already knew because, in 1859, one of the brothers, William, seems to have entertained dreams of setting himself up as squire, with the purchase of Plas Hengwrt at Llanelltud.

The tenure of the McConnels saw a major expansion of Bryneglwys quarry, and they built most of the older houses in today’s village. But again, this was done for sound economic reasons.

It was difficult recruiting workers in a sparsely-populated rural area, and so many people had to be persuaded to move to Abergynolwyn. They could not move without somewhere to live.

The McConnels therefore built and owned their workers’ houses, for which the workers paid rent. A common enough arrangement.

And seeing as we’re discussing slavery . . . plantation owners also built accommodation for their slaves.

The McConnels laid the railway line we know today as the Talyllyn Railway, done to get the slate out to their customers. By taking it down to the coast, from where it would either be transported by rail from Tywyn or by ship from Aberdyfi.

The line also brought supplies to Abergynolwyn. With a local network taking those supplies, particularly coal, around the village. The train also brought beer for the pub!

Sir Henry Haydn Jones kept the railway open as a passenger service after the quarry closed in 1947/48.

◊

‘SLAVERY’

I’m writing this because Abergynolwyn is the village in which I’ve lived for many years, where my children were brought up, and where my wife was born and raised. Her taid, Richard ‘Dic Bêch’ Humphreys, worked in the quarry.

But now the village is getting very unwelcome publicity due to being unfairly associated with slavery.

Here’s the Telegraph headline (29.04.2023).

And here’s the headline from the Spectator article (14.05.2023).

I don’t really feel particularly “embroiled“, but let’s be quite clear about this . . .

The community of Abergynolwyn has no connection with slavery other than a tenuous link provided by the McConnels, who came to Abergynolwyn when the American Civil War cut off their supplies of raw cotton.

Though it could be argued that the link between Abergynolwyn and slavery is even more tenuous seeing as the McConnels did not own slaves or plantations themselves.

Using the reasoning of extended culpability could it be argued that a baby wearing a garment made from McConnel cotton was also complicit in slavery?

And would guilt extend to someone living in a property roofed with Abergynolwyn slate?

Come on, let’s get real – this slavery accusation is just Woke bollocks. Heading in the direction of, “All White people are guilty!“.

You’ll note that the Telegraph headline mentions an “explanatory plaque“. Well, here it is, as it now appears on our Canolfan wall.

So who’s responsible for the wording on the plaque? Is it Cyngor Gwynedd? Cadw? Someone working for the so-called ‘Welsh Government’?

UPDATE: I now learn that the text on the plaque was written by the National Slate Museum, and knocked up by Headland Design, of Cheshire. How could a Welsh institution have got it so wrong? And why did an English company get the contract?

But it doesn’t end there for David Martin-Jones, the writer of the Spectator piece – who claims roots in the area – for he thinks he’s found another issue.

But McConnel is English and a capitalist to boot. Such a background is anathema to those who currently run Wales and micro-manage the Welsh version of the cultural revolution. From this perspective, McConnel’s achievements must be re-defined to fit an ideology that reduces history to melodrama, where brutal and rapacious English capitalists despoil the Welsh landscape and immiserate its people.

He sees the McConnels as victims of “the Welsh version of the cultural revolution”. And while I won’t argue with anyone putting the boot into our hyper-Woke ‘Welsh Government’, I will take issue with the suggestion of an anti-English motivation.

Listen, Dai, try reading that plaque again. Yes, there’s a silly reference to slavery, but apart from that where’s the criticism of the McConnels?

The real problem is the exclusive and fawning focus on the McConnels.

The McConnels took over an established Welsh business and the quarry ended its working life back in Welsh ownership. But that plaque is all, “McConnel, McConnel, McConnel . . . Manchester, Manchester, Manchester”.

◊

CONCLUSION

The plaque on our Canolfan insults the community with its unnecessary and misleading reference to slavery; while also being historically inaccurate in not mentioning the Welsh ownership.

Yet it could have been even worse.

For I understand that someone involved in designing the plaque was so keen to glorify the role of the McConnels that an earlier draft even tried to credit them with building the old village hall in 1947 – a full 36 years after they’d severed their ties with the area!

That plaque must be removed, and re-written. With the new plaque giving a more accurate resumé of the quarry’s history, and without any references that insult the memories of decent people who can no longer answer for themselves.

Because with the tourist hordes about to descend I’d hate to be approached by someone who’s read the plaque and then asks me if I’m suitably ashamed of the village’s links to slavery.

In such a situation I might let slip a naughty word. Perhaps a few naughty words.

♦ end ♦