Category: History

The day Thou gavest, Lord, is ended

Today marks the centenary of the Senghennydd mining disaster, the worst ever in the UK, that claimed the lives of 440 men and boys. It was commemorated with various events in Senghennydd including the unveiling of a statue remembering all who died in Welsh mining accidents.

Many who died at Senghennydd in 1913 had travelled there from other parts of Wales, but you wouldn’t have known that from reading this morning’s Wasting Mule, which did a panel piece on someone who’d moved from West Sussex! Doesn’t the Mule realise that the whole point of a Welsh newspaper is to cover Welsh news, and other news from a Welsh angle? Senghennydd provided an opportunity for the Mule to live up to its claim to be the ‘National Newspaper of Wales’ by bringing together the various parts of the country; but no, the Mule, as ever, had to look at Wales from an English perspective.

I mention this because I was fortunate enough to take part in a little ceremony of remembrance myself on Saturday. Due to my wife and her sister being collateral descendants of Edward Jones Humphreys of Abergynolwyn who, by the time he died at Senghennydd – and by a route the ladies have yet to establish – was universally known as ‘Idrisyn’. When the local quarry closed he made his way south with his brother (wife’s taid), and their sister, who was there with her husband. (Click to enlarge image.)

The fact is that W ales in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries experienced considerable internal migration which, for whatever reason, is often neglected. Too many prefer to concentrate – a la Mule – on migration into or out of Wales. Of my eight great-grandparents four came up to Swansea from the west, Carmarthenshire and Cardiganshire, places like Meidrim and New Quay. Most of those who came to work in the local Bryneglwys quarry here in south Meirionnydd came from Montgomeryshire, Caernarfonshire or further afield.

ales in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries experienced considerable internal migration which, for whatever reason, is often neglected. Too many prefer to concentrate – a la Mule – on migration into or out of Wales. Of my eight great-grandparents four came up to Swansea from the west, Carmarthenshire and Cardiganshire, places like Meidrim and New Quay. Most of those who came to work in the local Bryneglwys quarry here in south Meirionnydd came from Montgomeryshire, Caernarfonshire or further afield.

Returning to Senghennydd, I cannot avoid saying that I am disappointed with the statue. (Click to enlarge.) Isn’t it a bit, well, unimaginative? Crass, even? And another thing, the two portrayed are obviously survivors of some tragedy or other, so how do they commemorate the dead? Don’t get me wrong, I’m not saying that a statue commemorating the dead has to be composed of corpses, but this statue looks like the kind of ‘heroic’ and inspiring public art that could be found in every shit-hole town in the Urals circa 1965. It’s almost a caricature of communist propaganda statuary. In profile, the miner holding the lamp even has a passing resemblance to Lenin!

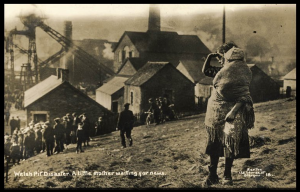

Surely the obvious inspiration for any statue commemorating the dead of Welsh mining disasters is that iconic image of the young girl, with the baby wrapped in a traditional shawl, shielding her eyes and looking into the distance. (Click to enlarge.) For these countless disasters may have taken the lives of thousands of  men and boys, but once dead they were – as my mamgu would say – ‘out of it’. The real suffering then was that of those who remained, the widows and orphans, so perfectly characterised by that sublime image. And, yes, it is also a memorial to the dead, for doesn’t she represent countless thousands of women and girls looking, waiting, for husbands, fathers, brothers who are never going to return?

men and boys, but once dead they were – as my mamgu would say – ‘out of it’. The real suffering then was that of those who remained, the widows and orphans, so perfectly characterised by that sublime image. And, yes, it is also a memorial to the dead, for doesn’t she represent countless thousands of women and girls looking, waiting, for husbands, fathers, brothers who are never going to return?

So why did the chosen statue have to be so in-yer-face? Did those who made the decision fear that visitors would be bewildered if confronted by anything needing a little thought and reflection? Isn’t that the whole point of art? Even public art?

A lot of sincere people in Senghennydd and the surrounding area have done a wonderful job of giving us another genuinely national institution. Making us all remember an important date in Welsh history, from a time and place that now seem so distant. They should all be proud of what they’ve done. Unfortunately . . . the centre-piece, the statue-memorial, was not an inspired choice. I’m sorry, folks, it was the wrong choice.

Guest Post: Jeremy Wood, Esquel, Patagonia

I am delighted to offer you something different, a piece by Jeremy Wood on an obscure publication relating to the Welsh settlement in Patagonia. Jeremy and I have never met but we have corresponded for quite a few years, having had a mutual friend in the late Rhobert ap Steffan (‘Castro’) who visited Patagonia a number of times over many years.

*******************************************************

Llawlyfr y Wladychfa Gymreig

With the 150th anniversary of the arrival in 1865 of the first Welsh migrants to Patagonia looming, an English translation of a long-forgotten document has recently come to light. The pamphlet was written by Hugh Hughes (Cadfan Gwynedd) in 1862, when the emigration project was being pilloried in the Welsh and English press, in an attempt to address the criticisms and explain the  project in detail. It was unearthed by Jeremy Wood, who lives in Esquel in Welsh Patagonia, in the Welsh museum in Gaiman in Patagonia. A number of copies of the Welsh-language original exist, but all are in museums, universities and libraries and the document has never been published on the internet nor have any detailed studies of it been published. Jeremy Wood digitally remastered the original work in Welsh and worked with Cynog Dafis, who produced an excellent English translation.

project in detail. It was unearthed by Jeremy Wood, who lives in Esquel in Welsh Patagonia, in the Welsh museum in Gaiman in Patagonia. A number of copies of the Welsh-language original exist, but all are in museums, universities and libraries and the document has never been published on the internet nor have any detailed studies of it been published. Jeremy Wood digitally remastered the original work in Welsh and worked with Cynog Dafis, who produced an excellent English translation.

The first part of the “brochure” explains why the Welsh should leave Wales and set up their own colony overseas. Hugh Hughes was a passionate Welshman and didn’t pull any punches. He filled the first 19 pages with anti-English invective of such intensity that its publication would surely test England’s anti-discrimination laws today. He put forward a passionate case for the capability of the Welsh to run their own country and addressed individually the major criticisms raised in the press. He then went on to quote more than 20 reference works from explorers, sea captains and settlers to give the potential emigrants a good idea of what sort of place they’d be settling in.

and addressed individually the major criticisms raised in the press. He then went on to quote more than 20 reference works from explorers, sea captains and settlers to give the potential emigrants a good idea of what sort of place they’d be settling in.

When one reads Hughes’ account of the sorry plight of Welsh citizens having to give up their language to have any chance of progressing in life and having to live under the thumb of the English in all walks of life, one wonders what our politicians have been doing for the last 150 years. His predictions of increased English dominance were remarkably prescient. But nothing much seems to have changed and the lessons we could have learned, we have ignored.

Had Hugh Hughes actually told the truth about Patagonia (he Bowdlerised almost every reference he quoted and made up the rest!), few would have been brave enough to sign up for the first voyage on the Mimosa. But, of course, the Welsh did emigrate to Patagonia and their language and culture is still very much alive there. Hugh Hughes was, and still is, a Patagonian hero. We could do with men cast from the same mould in Wales today.

A trilingual version of Hugh Hughes’s pamphlet is due to be published next year. In the meantime, feast your eyes on some of the extracts taken from the first few pages of the book. Stirring stuff, indeed!

Jeremy Wood can be contacted at jeremywood@welshpatagonia.com

Nechayev and the Revolutionary Catechism

Over the years I’ve read a great deal of nineteenth-century Russian literature. It was a golden age: giving us not just Pushkin, Tolstoy, Chekhov, Gogol, or my personal favourite, Dostoyevsky, but so many others who are perhaps less well known to us in the West: Turgenev (Fathers and Sons), Lermontov (A Hero of our Time), Aksakov (A Russian Gentleman), Kropotkin (Memoirs of a Revolutionist) and Herzen (Childhood Youth and Exile).

Outstanding literature from and about a people that seem to be very much like us, and yet are different. Maybe it’s this uncertainty about Russia and Russians, and their relationship to ‘Europe’, that gives their nineteenth-century literature its appeal. Here was a Christian country on the edge of Europe that freed its white slaves around the same time as the USA freed its black slaves. (Or at least, President  Lincoln ‘freed’ the slaves in Confederate-held territory.) An absolute monarchy where opposition was ruthlessly crushed, either by execution or else by being banished to Siberia, the almost incomprehensible emptiness that soon became a byword for exclusion, or a living death.

Lincoln ‘freed’ the slaves in Confederate-held territory.) An absolute monarchy where opposition was ruthlessly crushed, either by execution or else by being banished to Siberia, the almost incomprehensible emptiness that soon became a byword for exclusion, or a living death.

As I discovered in my long-ago reading tsarist Russia was a complex country where, for example, distance was measured in versts (1 verst = 3,500 feet). Why, I asked myself, did a country as vast as Russia use a measure of distance shorter than an English mile? And why were there so many bloody aristocrats? Answer: it went with the job. If you moved high enough up the imperial bureaucracy then, instead of getting the equivalent of an OBE, you reached the ranks of the nobility. Which I suppose is not really so strange when you recall that hereditary peerages were still being awarded (and sold) in England at this time, plus, of course, knighthoods. And while Church Slavonic could be equated with liturgical Latin, there was nothing in the West to compare to the Old Believers . . . or the Cossacks . . . and Tatars . . .

Yet there were comparisons to be made with other periods of great artistic creativity. For just as the Italian Renaissance took place to a backdrop of intrigue and butchery, so this great outpouring of Russian writing seemed to be prompted by the turbulence of the times. The French invasion forms the theme to Tolstoy’s War and Peace (and also inspired Tchaikovsky to write the 1812). With the empire expanding east and south there were constant frontier wars that saw new lands being conquered and exotic peoples brought under the rule of the Romanovs. This expansion brought Russia into contact with older empires such as Persia, China and Turkey. The British was another empire expanding Russia came into contact with; the bear and the lion amusing themselves playing the ‘Great Game‘. While in Europe there were the Poles, the Finns and other reluctant subjects to keep in check. But more than anything else, it was the political situation in Russia proper that inspired so many of her writers.

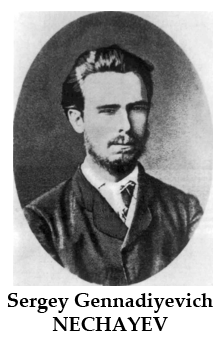

Perhaps even its staunchest defenders knew that the tsarist system was indefensible, but were too afraid to say so. Others were not. If we start with the romantic and doomed Decembrists of 1825 and end with the communist takeover of 1917, we have almost a century of opposition taking many different forms. All the great writers I’ve mentioned flourished within this same time frame. Yet of all the idealists, reformers, dreamers and revolutionaries one man stands out for his single-minded ruthlessness: the Anarcho-Nihilist, Sergey Gennadiyevich Nechayev. Let a couple of examples explain what I mean. In 1869 he got fellow-conspirators to sign a petition . . . which he then handed to the police, in order that the brutal treatment they’d receive would harden them! A comrade – Ivan Ivanovich Ivanov – who disagreed with Nechayev was strangled, shot and thrown into a frozen lake through a hole in the ice.

It would be easy to dismiss Nechayev as a lunatic, best forgotten. And indeed, he might have been forgotten had it not been for his legacy, Catechism of a Revolutionary. This remains one of the most chilling documents ever written. It is Nechayev’s manual, telling anyone who reads it what he or she must do, and become, to be the perfect revolutionary. The very first sentence tells you what to expect – “The revolutionary is a doomed man”. But this was a man who practised what he preached. While languishing in the Peter and Paul fortress prison his comrades wanted to break him out, but he told them to focus their energies on assassinating the Tsar. When General Potapov, head of the Okhrana, the tsarist secret police, offered him a deal if he turned traitor, Nechayev struck him across the face. As punishment, his hands and feet were chained, until the flesh began to rot.

offered him a deal if he turned traitor, Nechayev struck him across the face. As punishment, his hands and feet were chained, until the flesh began to rot.

Inevitably, Nechayev made it into a number of books. Most famously, The Devils (aka The Possessed), by Dostoyevsky. Though the Catechism itself might have been forgotten if it wasn’t regularly resurrected by fresh groups seeking radical change. Among them Young Italy, the Black Panthers, the Red Brigades. So read the Catechism for yourself, see how you measure up. Ask yourself, ‘Do I want to meet Nechayev’s standards’. The answer will almost certainly be ‘No’. (If it’s ‘Yes’, I don’t know you. Understand!) His one time associate Vera Zasulich who, in 1878, shot and almost killed Colonel Trepov, the police chief of St. Petersburg, said Nechayev “was not a product of our world but a stranger among us”. Many would agree.

The Catechism is available here in PDF format.