It says something for the education systems in Britain and Ireland that so few people have heard of one of the most important battles fought in these islands before Hastings. Indeed, if Brunanburh had ‘gone the other way’ there might never have been a battle in 1066, for there might not have been an England for William to conquer.

Let’s set the scene: Alfred the Great  of Wessex died in 899, and there is a tendency to think that before he died he had driven out the Danes and left a legacy of a prosperous and united England. Not quite. Alfred did indeed defeat the Danes, but all he did was save Wessex and by so doing avoid a complete Danish takeover, but on his death the Danes remained in control of much of England. Though Alfred had re-taken London in 886 and by so doing helped lay the foundations on which others could build, and he possibly saved the English nation from complete absorption, a terrible fate for any people.

of Wessex died in 899, and there is a tendency to think that before he died he had driven out the Danes and left a legacy of a prosperous and united England. Not quite. Alfred did indeed defeat the Danes, but all he did was save Wessex and by so doing avoid a complete Danish takeover, but on his death the Danes remained in control of much of England. Though Alfred had re-taken London in 886 and by so doing helped lay the foundations on which others could build, and he possibly saved the English nation from complete absorption, a terrible fate for any people.

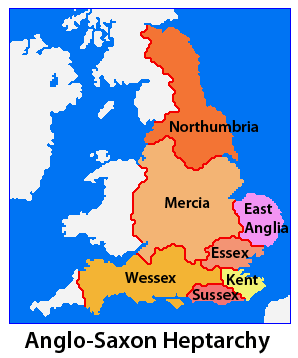

Alfred was merely king of Wessex, for this was the time of the heptarchy, England divided into the seven Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of Wessex, Mercia, Kent, Northumbria, East Anglia, Sussex and Essex. These had fluid boundaries and the picture was of course further confused by much of England, particularly the east and the north, still under Danish rule. For example, there may have been a king of Mercia, but he would probably have ruled west Mercia, as the east was under Danish control. The seven kingdoms are outlined in the map, which also shows an independent Cornwall and the northern boundary of Northumbria at Edinburgh, for Lothian – the old Gododdin – was not ceded to Scotland until the middle of the tenth century.

*

Despite Alfred and others calling themselves rulers of the English, the title meant little until the rise of his grandson Æthelstan. On the death of his father Edward the Elder in 924 Æthelstan became king of Wessex and effective ruler of much of England. Perhaps as a way of indicating his intentions, one of his first campaigns following his coronation in 925 was the annexation of Northumbria.

his coronation in 925 was the annexation of Northumbria.

On July 12, 927 Æthelstan called various rulers to Eamont Bridge, just south of Penrith, to acknowledge him as Bretwalda, or high king. Among those attending with Scottish and Pictish rulers were Owain of Strathclyde and Hywel ap Cadell of Deheubarth. This date is regarded by many as the end of the heptarchy and the beginning of modern England. The choice of Eamont may have been significant because the river Lowther that runs through the village could have been a political boundary at the time, perhaps the southern frontier of Strathclyde.

The same year saw Æthelstan capture York from the Danes, and call another gathering at Hereford. The purpose of which was to fix the Welsh border at the river Wye. In attendance, to accept Æthelstan as overlord, were Hywel of Deheubarth and Owain of Glywysing and Gwent. In 931 Owain’s successor, Morgan Hen (‘Old’), plus Hywel and Idwal Foel (‘the Bald’) of Gwynedd, were called to London to attend Æthelstan’s court as sub-kings. Just a few years later, in 934, Tewdwr of Brycheiniog was ‘invited’ to London to sign English land charters. While in the same year, Hywel of Deheubarth, Idwal of Gwynedd and Morgan Mwynfawr (‘the Wealthy’) of Morgannwg were compelled to accompany Æthelstan on his campaign against Constantine II of Alba.

In addition, he drove the Cornish from Exeter and fixed the boundary between English and Cornish at the Tamar, and was already issuing coins that described him as ‘King of all Britain’. You didn’t didn’t need to be a soothsayer to realise that Æthelstan had ambitions that went way beyond re-uniting the English. The question was, how should individual rulers respond to his ambitions?

Looking back from 2014, I guess the choices were: 1/ Submit, in the hope that English rule wouldn’t be too bad and that you wouldn’t be swallowed up by England. 2/ Accept Æthelstan as overlord in some fingers crossed sort of way and hope that full independence could be regained at some future date. 3/ Resist English encroachment and fight. Most of Æthelstan’s increasingly worried neighbours chose option 3.

2/ Accept Æthelstan as overlord in some fingers crossed sort of way and hope that full independence could be regained at some future date. 3/ Resist English encroachment and fight. Most of Æthelstan’s increasingly worried neighbours chose option 3.

Who was to be top dog in these islands was decided in 937 at the battle of Brunanburh. On the side opposing Æthelstan were Constantine II of Alba, Owain of Strathclyde, and Olaf Guthfrithson, Norse king of Dublin. Æthelstan’s army was exclusively English . . . apart from units volunteered by Hywel ap Cadell of Deheubarth. There is no reference in any of the accounts to Gwynedd being involved on either side.

For the tenth century, where battles tended to involve a few hundred men, Brunanburh was on a different scale entirely, possibly because – as some claim – it was pre-arranged. We know that thousands fought at Brunanburh, thousands died. Constantine’s son fell; two of Æthelstan’s cousins died; the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle says that five kings and seven earls died on the enemy side alone. Such was the scale of the battle that for decades afterwards the English referred to it as “the great war”. Though Æthelstan was victorious the enemy leaders all escaped; it may have been this, coupled with his great losses – or the reluctance of his followers – that meant he was unable to capitalise on the victory by pursuing and totally crushing his enemies.

*

Nations have been founded and empires brought down by a single battle, Brunanburh could have been another history-changing encounter. In reality, it changed very little, the protagonists went home and things carried on much as before. The one great consequence of Brunanburh was a united and strengthened England, free from any immediate threat, that would inevitably seek to dominate its neighbours in the years and centuries to come. In fact, this consequence of an English victory could have easily been predicted before the battle, for Æthelstan had left no one in any doubt of his intentions. That being so, how do we explain the reluctance of the Welsh to get involved in a battle so close to Wales?

The answer lies with Hywel ap Cadell of Deheubarth, better known today as Hywel Dda (‘the Good’), the most powerful ruler in Wales, who did so much to keep his more ‘headstrong’ compatriots in check, and remembered today as the codifier of Welsh laws. A complex character, an anglophile, yet by the end of his life Hywel ruled over an almost united and independent Wales . . . but it was ‘independent’ only for as long as the English allowed that pretence to linger. Like all men he faced many choices in his life, and Brunanburh was perhaps the one with the greatest potential for change.

Yet the potential of Brunanburh to change history could only have been realised by an English defeat. Which might have been achieved had Hywel ap Cadell sent his troops to fight with their Strathclyde cousins and the others, and allowed other Welsh rulers to do the same; for had they acted together English power might have been broken at Brunanburh. What would have emerged is impossible to say, but our ties with Strathclyde would certainly have been re-established, and the collapse of English control would also have allowed us to link up again with the Cornish and the Welsh east of the Tamar.

Yet today, Hywel ap Cadell, the good king Hywel Dda, serves as a role model for many Welsh of a ‘pragmatic’ political bent. He is held up as an example the rest of us should follow in our attitudes to England – not like that ‘nasty’ Llywelyn, or that ‘horrible’ Glyndŵr, nothing but medieval warlords, they are . . . butchers, look – ach y fi!. From a nationalist perspective, Hywel can be seen as the man who preferred to remain England’s loyal servant than to seize the opportunity of restoring his people to some of their former glory.